“I am being diminished. Whittled away, piece by piece… Great chunks of my past, detaching themselves like melting icebergs” – The Doctor, The Five Doctors

People have been underestimating Doctor Who for a very long time. In 1963, cautious BBC execs were reluctant to commit to more than 13 episodes of their new teatime adventure serial, and when Russell T Davies announced plans to bring the show back 40 years later, industry “experts” lined up to tell him it would never work. But has anyone ever been more wrong about Doctor Who than the BBC bean counters who, when asked to state on internal paperwork the reason why they were consigning so many of the programme’s early episodes to oblivion in the 1960s and 70s, wrote simply: No Further Interest.

No further interest? Half a century on, as fans eagerly await the arrival of new versions of The Evil of the Daleks and The Web of Fear, that’s a phrase that rings laughably hollow. Not just because the stories’ release on DVD and Blu-ray is evidence of a viable commercial interest in itself, but because their very existence is testament to the resourcefulness and tenacity of fans who, over the years, cared enough either to make off-air sound recordings, painstakingly recreate the lost footage in animated form or, in one case, track down a horde of Yetis in the hills of Nigeria.

The story of how so much of Doctor Who came to be lost in time – and how much of it eventually came back – is, in part, the story of television itself: one that goes to the heart of how much cultural capital we place on a medium once dismissed as “the idiot’s lantern”.

“I think there’s probably a rule of thumb that people don’t take a medium seriously until it’s 50 years old,” says Dick Fiddy, co-ordinator of Missing Believed Wiped, a British Film Institute initiative dedicated to recovering lost television material. “Certainly that’s what happened with film. Suddenly, there’s enough of a history for people to start investigating, and writing serious books about. And, I suppose, for people to start feeling nostalgic about.”

In the 1960s and 70s, BBC bosses could only see two possible reasons for retaining old episodes of Doctor Who: for domestic repeats and foreign sales. The former was limited by Equity and the Musicians’ Union to one second screening, after which the episodes were basically just taking up perfectly good, reusable videotape – no small consideration when a 60-minute tape would have cost the average British worker at least five weeks’ wages. Hence the issuing of those charmingly named Wipe/Junk Authorisation forms (they of the ‘No Further Interest’ notoriety), which sealed the fate of dozens of original two-inch video tapes of Doctor Who between 1967 and 1974.

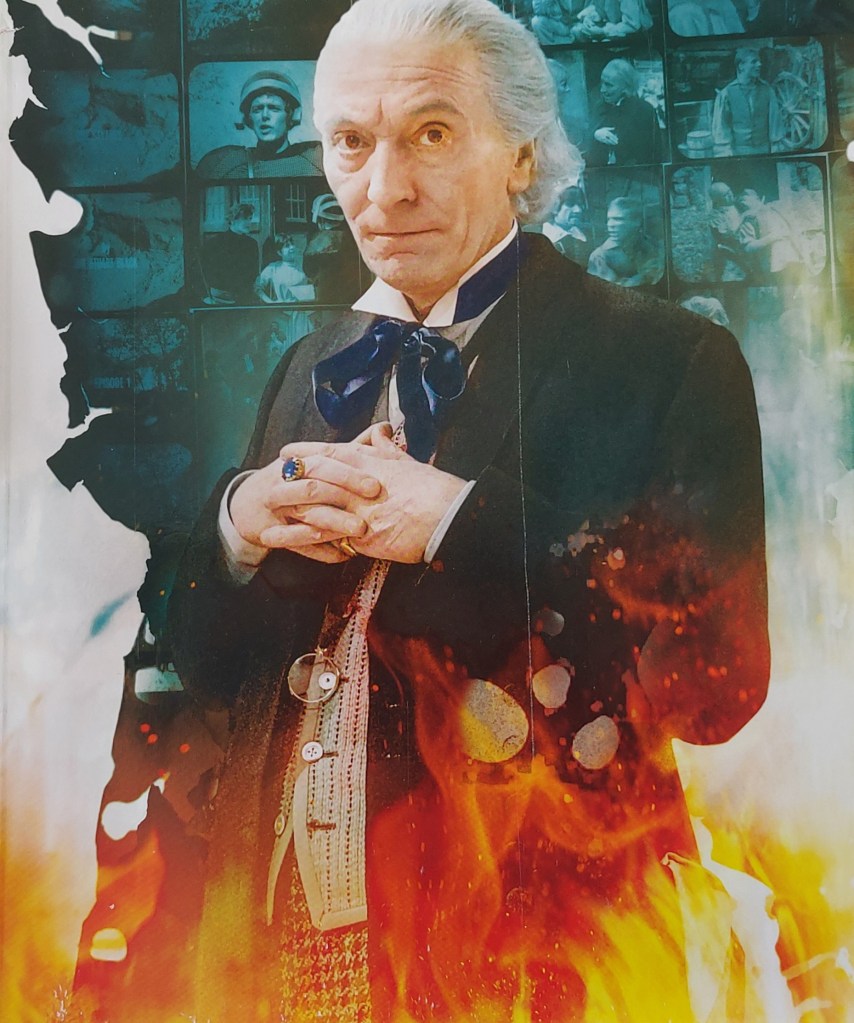

Certainly the people making Doctor Who in the 1960s weren’t entertaining lofty thoughts of the show’s legacy: their job was just to make 25 minutes of entertainment to (all together now) fill the gap between Grandstand and Juke Box Jury. “There was no question of it being kept,” says Anneke Wills, who played companion Polly alongside William Hartnell and Patrick Troughton’s Doctors. “It was just the nature of television in those days – practically all your work was ditched when you’d finished it.”

“It only seems ridiculous to us now,” agrees Dick Fiddy. “At the time it would have made perfect sense. Can you imagine if the newspapers had found out the BBC was sitting on a hundred thousand video tapes, and instead of re-using them, was using licence payers’ money to buy new ones? So you can’t play the blame game. I always say the search for lost stories should be a treasure hunt, not a witch hunt.”

If domestic repeats were a non-starter, foreign sales were a potentially more lucrative cash cow (it’s no accident that BBC Enterprises, the corporation’s commercial sales division, began life as the tellingly named BBC Exploitation). To get round the problem of countries using different broadcast formats, it was standard practice to make black and white, 16mm film telerecordings of the original two-inch videotapes (a practice that continued well into the Third Doctor’s run, which is why so many of those early 70s stories only survived in monochrome, until some very clever fans came up with ingenious, borderline magical ways to put the colour back into Jon Pertwee’s cheeks).

This global scattering of the Doctor Who seed is the reason so many lost episodes have subsequently been returned to the archives, often turning up in the most unlikely places, be it a TV station in Africa or, in the case of The Lion, from 1965’s The Crusade, plucked from the jaws of death on a New Zealand landfill site.

In time, as black and white TV fell out of fashion and overseas broadcast rights expired, buyers had the choice of either returning the film cans to the BBC or destroying them. Fortunately for us, these rules don’t always seem to have been rigorously adhered to – presumably some countries that were in the grip of actual civil war had more pressing things to worry about – which is just as well, as BBC Enterprises ended up tossing many of the ones that did come back into a skip. (That’s not a metaphorical skip, by the way: it was an actual skip, outside BBC Enterprises’ offices in Ealing, the contents of which were then sent to an incinerator.)

If the decision to re-use the original two-inch master tapes makes a sort of sense, what’s less easy to understand is why the BBC was still destroying film copies of Doctor Who (which had no re-use value anyway) until as late as 1977. This was the same year, lest we forget, that BBC2’s Lively Arts strand dedicated a whole programme to examining Doctor Who as a cultural phenomenon, a year after the formation of the Doctor Who Appreciation Society and a whole four years since the Radio Times Doctor Who 10thanniversary special had chronicled all the Doctor’s previous adventures to a generation who had no idea that, behind closed doors, they were gradually being erased from existence.

As secretary of the Doctor Who Fan Club in the early 70s, Keith Miller was in no doubt about his members’ interest in the series’ history. “That’s why I started documenting the episodes from the beginning,” he says. “Which didn’t go down well with Jon Pertwee. He kept saying, ‘It’s my programme now, it’s got nothing to do with them! [William Hartnell and Patrick Troughton]’. But I thought, no, it’s Doctor Who, it’s got everything to do with them.”

And yet the BBC was still wiping the tapes – even, incredibly, of Jon Pertwee’s episodes. “It took the BBC a long time to catch up with the fact there was a paying audience out there, willing to keep Doctor Who alive,” says Keith.

As with many large and unwieldy institutions, it’s possible that one arm of the BBC simply had no idea what the other was up to: so the Engineering Department, which was responsible for wiping the two-inch videotapes, might have been doing so secure in the knowledge Enterprises had already made film transfers, while Enterprises may have been oblivious to the fact those film cans contained the last copies in existence. But the truth is no-one really cared enough to find out – at least until Sue Malden was appointed as the BBC Film Library’s first Archive Selecter in 1978 and, in a stroke of good fortune, chose Doctor Who as her template to investigate the scale of the archive’s depleted stock.

A few years later, Sue was visited at the library by Jeremy Bentham of Doctor Who Magazine (or Doctor Who Monthly, as it was then), and it was his seminal report in DWM’s 1981 Winter Special that first laid bare the tragedy of Doctor Who’s vanishing past.

“There was that one-page listing, with all these mysterious annotations next to them,” recalls Richard Molesworth, author of acclaimed book Wiped! Doctor Who’s Missing Episodes. “Things like: Marco Polo – none, The Web of Fear – 1, The Tenth Planet – 1,2,3… I just couldn’t work out how we’d arrived at a situation where no episodes of The Power of the Daleks or The Tomb of the Cybermen existed. All these wonderful stories I’d been too young to see but had read about in the Radio Times special… It was mortifying. It was the first time the enormity of what was missing was crystallised, in that one page of text.”

Jeremy Bentham himself had first got wind of the problem a few years earlier when producer Tony Cash’s team were sourcing clips for the Lively Arts documentary in late 1976. “When his researchers had gone through the film library, that was the revelation,” says Jeremy. “Until then there’d been a bland assumption that everything did exist on the shelves somewhere.”

In the article, Jeremy vividly likens the library to ‘some huge Pharoah’s tomb – a storehouse of treasures kept safe from the ravages of time’. “There was a little bit of that Howard Carter feeling,” he laughs today. “Of being inside the tomb and seeing wonderful things…” Except, as we know, quite a lot of treasures had not been kept safe from the ravages of time, nor indeed the ravages of BBC economics.

Thankfully, Jeremy wasn’t the first Doctor Who fan to take a poke around the BBC’s archives: in 1977, a lucky eleventh-hour intervention by Ian Levine almost certainly stopped hours more of the Doctor’s adventures being consigned to the flames. The story of how Ian walked into BBC Enterprises’ storeroom at Villier’s House to find all seven episodes of the first Dalek story taped up and labelled WITHDRAWN, DE-ACCESSIONED AND JUNKED is the stuff of legend and, having rescued that priceless piece of television history from the incinerator, he went on to discover film copies of a further 56 Hartnell and five Troughton episodes. (With trademark stubborn tenacity, when copyright rules prevented him from making a private purchase of the episodes, Ian simply went directly to Equity and The Writers’ Guild and negotiated himself a special dispensation.)

For Ian, it was the start of a long journey of tracking down lost Doctor Who stories – not just from the vaults of the BBC, but from all over the world. In 1984, a chance remark on Radio 2 about Nigerian television being so behind the times that “Patrick Troughton was still Doctor Who” prompted him to begin calling up TV stations there (a country, lest we forget, beset by decades of war and civil unrest, which had just been seized by yet another military junta). This somewhat unlikely punt resulted in the recovery of three episodes apiece of The Time Meddler and The War Machines – though their return was further delayed when the kidnap of a former Nigerian government minister in London created something of a diplomatic incident.

After that, Ian began sending telexes to TV stations in every country known to have bought Doctor Who: legend has it that one in Iran responded with: “In the name of Allah, what are you talking about?”. Which is fair enough.

“As any collector will tell you, sometimes the thrill is in the hunt…”

Other fans soon followed in Ian’s wake – among them Paul Vanezis. Now best known by fans for returning episodes to their former glory as part of the Doctor Who Restoration Team, in 1984 Paul used his Cypriot heritage to contact a TV station in Cyprus – and, as much to his surprise as anyone’s, promptly turned up three lost episodes of The Reign of Terror.

“My interest was purely selfish,” admits Paul. “I just wanted to see them. I didn’t really care if anybody else got to see them. It was just annoyance, really, at the thought these stories that had been so mythologised no longer existed.”

Other recoveries felt more like a gift from the gods: in 1983, cans of film containing episodes five and 10 of The Daleks’ Master Plan were found in the cellar of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Wandsworth. Or it may have been the Mormon Unification Church in Clapham. Or at least near Clapham – the recollections vary to such an extent, many believed the actual source was comedy legend, and avid film collector, Bob Monkhouse. (It almost certainly wasn’t, says Dick Fiddy.)

Others were more prosaic: Episode two of The Daleks’ Master Plan was returned after spending 20 years in broadcast engineer Francis Watson’s cupboard, then a further decade in a carrier bag hanging on a coat hook in his office at Yorkshire Television in Leeds. Air Lock, the episode of Galaxy Four recovered in 2011, had been acquired at a school fete in Southampton three decades earlier, while The Evil of the Daleks episode two and The Faceless Ones 3 were picked up at a film fair in Buckingham.

The latter find led to a memorable afternoon when Paul Vanezis and fellow organisers of 1987’s TellyCon convention in Birmingham were able to surprise the audience with an emotionally-charged screening of the Faceless Ones episode: the Second Doctor, returned to us from the ether, 20 years after the episode’s first broadcast – and just three weeks after Patrick Troughton’s death. “It was a magical moment,” says Richard Molesworth, who was in the audience (having missed an earlier private screening for the event’s stewards because he had to go home and do his paper round).

All of which begs the question: In an age when every existing Doctor Who episode is available to stream on your smartphone, is there perhaps something to be said for those days, when tapes of old stories changed hands on an illicit underground network, and you had to go to the equivalent of an Doctor Who speakeasy in order to source a degraded, fifth-generation copy of The Wheel in Space part 3? And if no Doctor Who episodes had ever been lost in the vortex in the first place, might the lives of a generation of fans been a bit more… dull?

“If all the episodes had been there from day one, that would be slightly boring,” admits Richard Molesworth. “If they all turned up tomorrow, that would be rather jolly. But would I swap all those years of writing the lists and ticking them off? Probably not, because that was kind of fun, too.” “As any comics collector will tell you, sometimes the thrill is in the hunt,” agrees Jeremy Bentham.

For many years, 1967’s The Tomb of the Cybermen was the Holy Grail of lost Doctor Who stories – so its discovery at a TV station in Hong Kong in 1991 sent a seismic tremor through fandom. But this prize haul almost got lost all over again: having been posted back to the BBC from Asia Television, the films went AWOL for a month, and were eventually discovered – with nothing to identify them save for the story’s original production code (MM) – lying unclaimed in the loading bay of the BBC’s Woodlands depot.

Rush-released on BBC Video, The Tomb of the Cybermen shot to the top of the video charts in 1992, its 24,000 copies leaving Kevin Costner’s Robin Hood and Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter trailing in its dust. No Further Interest? Pah.

Since DWM listed that shocking total of 136 missing Doctor Who episodes in 1981, 39 have been returned, taking the tally below the magic 100 barrier, to 97. That is a minor miracle in itself – and a huge credit to all the people who have invested time, energy and resources into the search. “It amazes me to this day that so much work has been undertaken by so many people – often just out of a sense of love for it,” says Jeremy Bentham.

But since 2013 – when archive recovery specialist (and self-styled “real Indiana Jones”) Philip Morris discovered nine lost episodes from Second Doctor stories The Web of Fear and The Enemy of the World in Nigeria – there has been a worrying radio silence. Is it simply a case of, the more leads that are followed up, the smaller the window of opportunity becomes?

Not necessarily. “This is all about trust,” says Paul Vanezis. “Philip managed to find a way of getting those episodes back that didn’t involve bribery – which is often what you’re up against in Nigeria – because he’d worked in the oil industry, he knew how it worked out there. Going out there and establishing contacts will get you a lot further than making telephone calls.” [In a further twist to the tale, Philip Morris later claimed that the still-missing Web of Fear episode 3 had been among his Nigerian discovery, but had subsequently gone missing…]

Closer to home, Jeremy Bentham is keeping a weather eye on other potential leads, including film copies that may have been sent to the Royal Navy for ship and submarine crews to watch, and the somewhat ghoulish reality that, as the first generation of TV film collectors begins to die off, their stock might go up for sale or donation. (“Often, it’s nothing to do with people being secretive,” notes Dick Fiddy. “It’s just that people don’t know what they’ve got.”)

So if there are more episodes out there, what might we actually one day get to see? Received wisdom has it that 1964’s Marco Polo, the oldest missing story, is the most “likely” – in very large, flashing quotation marks – to come back, simply because more foreign broadcasters bought Doctor Who’s earliest run: the serial was sold to 25 countries, compared to just one for The Daleks’ Master Plan – meaning only one film print of Master Plan was ever struck.

And yet, look at what’s actually turned up: of all the episodes discovered over the past four decades, only a handful are from the early Hartnell years (which, to be fair, are well represented in the archives anyway), while seasons three and, in particular, five have benefited from a positive goldrush (with the happy result that more than half of the once threadbare Patrick Troughton era has now been restored).

“The truth is, there’s no point trying to be scientific about it – anything could turn up at any time,” says Paul Vanezis. “Where did Philip Morris find The Web of Fear and The Enemy of the World? In the last place they were screened. That’s always the place to start, and then you work backwards from there.”

One reason the breadcrumb trail is so complicated is due to the historic use of a “bicycling” system, under which broadcasters would pass their films onto different countries at the behest of the BBC. “The War Machines [recovered in Nigeria in 1984] went from New Zealand to Singapore, along with a whole bunch of other season three and four stories,” explains Paul. “That story was on a palette with The Savages, The Smugglers, The Tenth Planet, Power of the Daleks… So the question is, where were those films between the screening in Singapore and The War Machines ending up in Nigeria?

“Or take The Tomb of the Cybermen. When you look at the paperwork, it makes perfect sense that that story was left behind in Hong Kong. But the same paperwork tells you The Evil of the Daleks should be there too. So where’s that gone?”

As tantalising as all this is, there’s something of a ticking timebomb in the fact that, the longer 35mm film stock goes undiscovered, the more it risks becoming degraded beyond use. So there’s a race against time element to this treasure hunt, too. Nevertheless, most people in the Doctor Who recovery business continue to travel hopefully that the universe will surprise us with more discoveries.

“You’ve always got to be optimistic,” says Richard Molesworth. “You’ve always got to think there’s more to be found. But at the same time, we’re never going to know when we’ve found the last missing episode. We may already have hit that point.”

“I’ve still got my original list from 1981, when for a long time it was 136 episodes, and we were firmly convinced it was never going to drop below that,” says Jeremy Bentham. “Now, you’ve only got to look at the number of crossings out. So I live in hope.”

“I never stop being surprised by the things that happen in the Doctor Who world,” says Anneke Wills. “You never know. I wouldn’t close the door – because this show has its own magic…”

…………………………………………………………

Missing… ish

While 97 episodes of Doctor Who are still missing, it would be a mistake to say they are entirely lost. Thanks to fans like Richard Landen and the late Graham Strong, among others, we are blessed with complete off-air audio recordings of every story ever made.

While that’s not unique – taping pop music and comedy programmes, in particular, was common practice in the 1960s, says Dick Fiddy – Doctor Who is unusually well represented for a drama serial. “If it wasn’t for those fans lying on their tummies and recording the stories, we wouldn’t have the soundtracks at all, so hooray for them,” says Anneke Wills.

There are also surprisingly good visual records of many missing episodes, thanks to John Cura, a freelance photographer who had an arrangement with the BBC to supply off-air ‘tele-snaps’ of various productions. “Seeing those for the first time was incredible,” says Jeremy Bentham, who discovered the first batch while researching his 1986 book Doctor Who: The Early Years. “There was a time when old photographs of Doctor Who weren’t that common, so that was a real treasure trove.”

By matching these tele-snaps to the off-air soundtrack, fans have been able to enjoy at least an approximation of the missing episodes – an experience that’s now been taken to a new level with the creation of fully animated reconstructions.

“I was once interviewed by a newspaper journalist who said, ‘There are all these episodes of Doctor Who you know nothing about,” recalls Richard Molesworth. “They were amazed when I said, ‘Actually we know practically everything about them: we’ve got audios, tele-snaps, copies of the scripts… The only thing we can’t do is see them!”

…………………………………………………………

“It’s no good crying over spilt milk…”

In one sense, the absence of so much early Doctor Who is a tragedy – but does it also add to the programme’s mythos and mystique?

“I like your thinking – I like to be mysterious, you know,” laughs Anneke Wills. “I’ve come to accept it over the years,” she adds, of the fact no fewer than 27 of her 40 episodes still remain lost. “It’s no good crying over spilt milk. My duty is to fill in the gaps as much as possible.”

Is there a particular story she’d like to see returned to the vaults? “I think The Power of the Daleks, when we first meet Pat,” she says. “We met the Daleks as well, of course, but it was meeting Pat that stands out. The first regeneration was an AMAZING THING – can you put that bit in capitals? Pat was very brave to do it. So I’d love to be able to see that, and transport myself back. It would be amazing. But they’d better hurry up, ’cos I’m getting old…”

What would Pat have made, does she think, of the recovery of nine of his episodes making headline news – and the front page of the Daily Mirror – in 2013? “He’d have been tickled pink,” says Anneke. “Absolutely chuckling away on his cloud. But I can also hear him asking about the money!”

This article was originally published in Doctor Who Magazine issue 568, August 2021